Designing new instream structures

Introduction

Any new structure in a stream must be properly designed and constructed to allow appropriate fish passage up and downstream.Choosing an instream structure

The best instream structure for a particular location will depend on the purpose of the structure and the local conditions.

Order of preference for road crossing design

An instream structure should:

- allow all aquatic organisms and life stages to move safely and efficiently up and downstream

- have diverse physical habitats and hydraulic conditions (riffles, backwaters and areas of slow flow for example)

- not impede fish movement any more than adjacent stream reaches without structures

- allow natural processes like the movement of sediment and debris to continue

- be durable and require minimal maintenance.

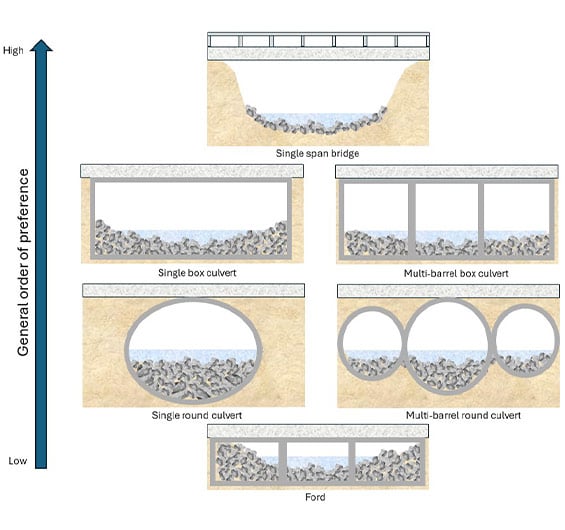

The diagram above shows the order of preference for road crossing design, based on the degree of connectivity each design facilitates.

- Fords are the least preferred type of river crossing. The bed and banks are typically artificial, water is shallow and fast flowing, and there is often a vertical barrier at the downstream end.

- Different types of culverts have differing levels of impact on fish passage.

- Bridges are the most preferred type of river crossing. They preserve the natural stream bed and banks, and allow natural water depths and velocities to be maintained.

See section 4 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines for design guidance on new and replacement instream structures.

Design process

A process to guide the design and construction of new structures in streams is set out below.

- Assess the site to understand the requirements and risks.

- Set the ecological objectives and the performance standards for biology and water flow.

- Carry out a detailed site survey to inform the design.

- Design a concept structure that meets the objectives and standards set out in the Fish Passage guidelines, then complete the structural drawings and specifications.

- Obtain the approvals required

- Build the structure to specification, using an expert like a fish ecologist to oversee the process.

- Monitor and maintain the structure regularly to make sure it is in good order and continues to meet the objectives and standards.

See section 3 and 4 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines.

Culvert design

Culverts are commonly used to allow a stream to flow under a road or other structure. In most locations they can be designed, installed and maintained to provide for fish passage. Culverts must not impede fish passage unless an exemption has been approved by DOC.

There are three general approaches for accommodating fish passage in culverts.

- A basic method intended for culverts in small, low gradient streams or drains, where the road or access embankment does not effectively modify the floodplain.

- A standard approach that will be applied for most culverts, especially where larger streams or higher embankments are involved.

- An approach for culverts in steeper terrain, especially when the culvert crossings will be at higher elevations.

See section 4.5 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines.

Weir design

Weirs are used for a variety of purposes, such as managing water intakes and gauging flows, but they often impede the movement of fish. Where possible, weirs should be built as full river width with a natural rock-ramp fishway, instead of a conventional solid weir structure.

If it is not practical to build a rock-ramp fishway, a V-shaped broad crested weir with a baffled surface or a weir with a bypass channel should be considered.

Good design principles include:

- The top or crest of a weir should be round and broad.

- The weir should have a V-shaped lateral profile that has shallow, slow-flowing wetted margins on the weir face across the fish passage design flow range.

- Diverse flow environments should be provided, including wetted margins.

- Make the slope of the downstream weir face as gentle as possible.

- Use roughness on the face of the weir.

- A fish facility should be included if the weir face does not provide passage.

Design features to avoid:

- steep hydraulic drops and undershot weirs

- vertical wing walls

- back-watered upstream habitats.

See section 4.7 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines.

Ford design

Fords are the least preferred type of river or stream modification because they often hinder or block fish passage. Fords combine many of the negative aspects of culverts and weirs (like fast-flowing, shallow water, a sharp crest and a steep downstream face). Fords also modify the stream bed and allow vehicles and animals to enter a waterway.

It is best practice to avoid using fords for stream crossings if possible. But if a ford is the only viable option, it should be designed with features that allow fish to pass. These include ensuring a continuous pathway for fish passage is maintained across the structure at all flows.

Causeway ford designs that incorporate culverts are the minimum standard for fords – these should follow the guidance for culvert design. A ford must not impede fish passage unless an exemption has been approved by DOC.

See section 4.6 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines.

Flood and tide gate design

Flood gates and tide gates are used to control fluctuations in water flow during floods and tides. All tide and flood gates are considered barriers to fish passage. They can significantly disrupt movements of freshwater fish and invertebrates as well as the habitats upstream.

The characteristics of tide and flood gates that present problems for the movement of fish include:

- the duration the gate is open

- the size of the opening when the gate is open

- the velocity of water passing through the gate when the gate is open

- the depth of the opening when the gate is open

- the timing of gate opening relative to tidal stage (eg, flood and ebb).

When flood or tide gates are required, best practice is to install automated active gates that close only when the water level reaches a critical height. If operational constraints mean that the use of automated gate systems is not possible, the minimum standard is to install self-regulating ‘fish friendly’ gates. These gates should be kept open as far as possible for as long as possible (usually with a designed stiffener), particularly on the incoming tide as this is when most juvenile fish are moving upstream.

As well as improving fish passage, fish friendly gates allow better water movement up and downstream, and help to reduce the impacts on habitats (like salt marshes) upstream of the gate.

See section 4.8 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines.

Pump station design

A pump station is a site that hosts one or more motorised pumps that push water over or through a stop bank to prevent land from flooding.

A range of fish friendly pumps are available that can provide fish passage.

See section 4.9 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines and Improving fish passage at pump stations (PDF, 543K) for advice.

Stormwater management ponds

Stormwater management ponds/wetlands are designed to reduce downstream flooding and erosion in urban and other highly modified catchments.

When creating new stormwater management systems, the recommended best practice is to:

- utilise dry detention ponds, or

- develop an ‘off-line’ wet pond system.

In general, fish should be excluded from these systems due to poor habitat quality.

See section 4.10 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines.

Water intake design

Water intakes located within waterways that support freshwater fish need to be designed to prevent impingement and/or entrainment of fish. All new dams or diversion structures need to apply to DOC to determine if a fish facility is required.

Good design should consider a whole of intake design approach including:

- Water intakes being located to minimise exposure of fish to the screen and minimises the length of stream channel affected while providing the best possible conditions for the other criteria.

- Through-screen water velocity should be slow enough for fish to escape; a maximum of 0.1 ms-1.

- Sweeping velocity going past the screen should sweep fish past and back into the active waterway; be equal or greater than the approach velocity (>0.5 ms-1).

- Effective escape route (bypass) should be provided ensuring fish can return undamaged to the main stem (connectivity).

- Screening material and other joins/gaps have a maximum screen material opening size of 2-3 mm should be included to ensure protection of most freshwater fish.

- The intake or screen does not impede upstream passage through the wider waterway and does not increase the risk of predation or the bypass outlet keeps fish in the natural waterway.

If all criteria can not be met then consideration should be given to further strengthen some criteria over others.

See fish screen design for water intakes resources for more guidance.

Dams

Dams include any type of barrier that crosses a river or stream channel with the function of impounding or diverting water. These structures obstruct the natural free flow of water, the natural passage of fish, sediment, and other essential nutrients in river system. All new dams or diversion structures need to apply to DOC to determine if a fish facility is required.

See section 7 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines for guidance on how to provide upstream and downstream passage at dams greater than 4 m high.

Monitoring

Monitoring is the only way to understand how well a structure is working and ensure that any reduction in fish passage is not harming upstream or downstream communities. Monitoring is especially important when:

- rare or high value fish communities or ecosystems are upstream of the structure

- unproven designs or fixes are being used

- proven design is being used in a new situation

- retrofit solutions form only one component of an instream structure

- multiple structures exist within a waterway, causing cumulative effects

- barriers are being used to manage the movement of undesirable species.

See Chapter 8 of the New Zealand Fish Passage Guidelines or Fish Passage Monitoring Manual for more information about monitoring techniques and methods for evaluating the success of fish passage in different circumstances. The fish passage assessment tool can also be used to monitor the structure and the risk to fish passage.