Signs of takahē

Historic remains show that takahē were once widespread, living from sea level to the sub-alpine in areas of native grassland.

There were two species of takahē in New Zealand.

- South Island takahē

- North Island takahē/mōho, which is now extinct

Takahē numbers declined as glaciers retreated and forests regenerated, reducing their grassland habitat. Pressure from hunting and introduced predators that preyed on takahē, their eggs and chicks, reduced the population further. Introduced species, such as deer, were competition for food and habitat.

This led to few sightings by early Europeans suggesting that population was small and living in isolated pockets. Takahē were believed to be extinct, not once, but twice. The first in 1850, then in 1898 until they were rediscovered on 20 November 1948. Because of this, takahē are a true Lazarus species, defined as a species once thought to be extinct only to be rediscovered.

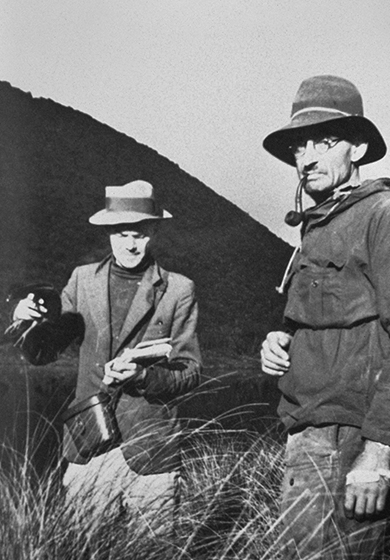

Takahē expedition, photo of Dr R. Falla (left) holding takahe chick and Dr G.B. Orbell (right), Takahē Valley, Fiordland.

Image: Daryl Eason | DOC

An obsession

The takahē is a gift (taonga) for all New Zealander’s today, due to one man’s obsession.

“Only four takahē had been found prior to 1898 and it was now supposed to be extinct. That word ‘supposed’ stimulated my boyish sense of adventure.” Dr Geoffrey Orbell

These were the words Geoffrey Orbell heard as a boy. He became intrigued with takahē. Orbell trained as a doctor and moved to Invercargill. He was a keen hunter, knowing the last sightings of takahē were in Fiordland, he combined his interests, hunting for both deer, and for the elusive takahē or what people fondly called, the ‘blue goose.’

Years of studying maps and tracking sightings, pointed him towards the Murchison Mountains/Te Puhi a Noa, being a place where takahē may have survived. The Murchison Mountains is a large mainland peninsula on the western shores of Lake Te Anau, rugged and barely explored.

Rediscovery

Orbell planned a hunting trip in April 1948, to the Murchison Mountains, with friends Neil McCrostie and Rex Watson. The group followed the Tunnel Burn to open tops where they looked down to a sub-alpine valley and lake, known by Māori as Te Wai-o-Pani. The party separated to stalk deer within the valley.

Orbell was resting when he noted an unfamiliar call, deep and long. “…the calls sounded as if someone were making a whistling noise by blowing across an empty .303 cartridge case.” The party retreated through the valley, following the shore of the lake. Orbell saw fresh bird tracks in the sand. Using his pipe, he etched the size of the footprint so he could measure it later.

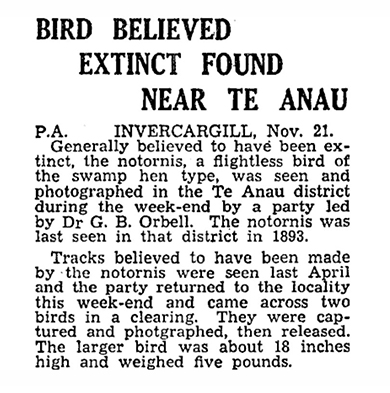

Otago Daily Times 22 November 1948.

Image: Otago Daily Times | ©

Excitement grew as Orbell measured the footprints and compared them to existing knowledge of the takahē. He shared this information with professors but while he was convinced of his find, others were not so sure. When he heard that another party was mounting an expedition, he gathered Neil and Rex, with the addition of Joan Watson (nee Telfer) to return to Te Wai-o-Pani.

The party arrived in a snow grass clearing in takahē valley. Within minutes, they spotted a takahē. Orbell, armed with a movie camera, took footage of what was by then two birds. A net was carefully placed around the birds which allowed them to be caught and details recorded.

“...the colouring was truly glorious - crayfish red beak, legs and feet; navy-blue head and breast, turquoise over the back, lower teal-blue, and finally tail-feathers in olive green.” Dr Geoffrey Orbell

It was the day Dr Geoffrey Orbell had dreamed of - takahē were extinct no more! 20 November 1948, the day of rediscovery, was the beginning takahē recovery. The news was met with excitement and headlines around the world.

Reference: Ballance, A. 2023. Takahē: Bird of Dreams. Potton & Burton.

Early research

Much of the early effort was spent understanding:

- how many birds were left

- how well were they doing and the pressures on the population

- what could be done to help them.

Researchers estimated the population as between 80 to 500. Somewhere in the middle was probably closer to the truth.

They quickly learned that the last remaining population was in trouble. The natural harshness of their refuge made life tough, along with introduced threats such as deer and stoats. By the 1980s, investment in more intensive management of populations had increased and the Burwood Takahe Centre was opened. An important step, Burwood remains the hub of takahe recovery today.

Hand rearing

Feeding chicks with a puppet 1990.

Image: Gerald Cubitt | DOC

Wild takahē struggled to raise two chicks at the same time. This presented the opportunity to support the population by raising chicks in the safety of the Burwood Takahē Centre and then releasing them into the wild in spring. This method tripled the young takahē's chance of survival.

Over twenty-five years of hand-rearing, fostering, and using hand-puppets, more than 400 takahē were raised, boosting the Murchison Mountains population and establishing crucial sanctuary sites for the Takahē Recovery Programme. However, the need to increase takahē numbers, the intensive resources required for hand rearing—including feeding chicks every 25 minutes—and concerns about the parenting abilities of hand-reared chicks led to a new approach.

In 2010, the Burwood Takahē Centre was improved and expanded to house a larger resident takahē population. This allowed the birds to hatch and raise their chicks naturally, without human intervention. This model remains in place today and has been fundamental to the ongoing success of the takahē recovery.

Timeline

- 1948 – Takahē rediscovered in the remote Murchison Mountains/Te Puhi-a-noa by Geoffrey Orbell and his party.

- 1985 – Burwood Takahē Centre created where wild eggs were artificially incubated, and puppet reared before being returned to the wild population.

- 1981 – Focus on natural history until population decline noted, lowest recorded population number.

- 1980s to 90s – Focus on establishing security population on four predator free islands (Te Hoiere, Mana, Kapiti and Tiritiri Matangi).

- 2007 – Large stoat plague event leads to the Murchison Mountain population being halved.

- 2010 – Puppet rearing stopped, moved to model of captive parent-raised birds at Burwood and sanctuary sites.

- 2016 – Total takahē population reaches 300. Population recovery finally back to pre-2007 stoat plague level and consistent population growth.

- 2018 – Reintroduced takahē into Kahurangi National Park with hope of establishing a second wild population.

- 2023 – Takahē population reached 500 and takahē are returned to the wild in the Upper Whakatipu, on Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu whenua, Greenstone Station to establish a second wild population.